November 30, 2015

Holiday Greetings / What’s In a Name?

Before there was digital technology that allowed for easy cutting and pasting of text, you had to do it the hard way. Hundreds of times over, our annotator demonstrates the old fashioned way of taking text from one place and adding it to another.

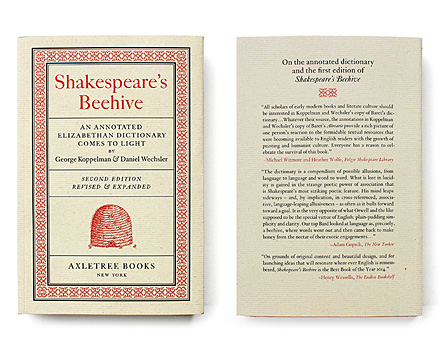

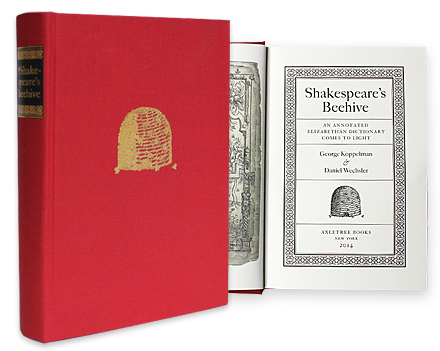

In this example from our chapter “What’s In a Name”, newly added to our second edition, we find a possible connection to one of the most memorable comic scenes in all of Shakespeare. It is just one of many new additions that appear throughout the second edition of Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light.

We continue to encourage members of the Beehive community to read our study and to share with friends the wonderful possibility that it argues for. Still thinking of the perfect gift for yourself or your fellow Shakespeare fan? Look no further!

– –

There is example for’t: the Lady of the Strachy,

married the yeoman of the wardrobe.

– Twelfth Night, Malvolio, Act 2, Scene 5

“The evidence, at all events, is insufficient to justify an excision of the sentence, however one might wish to justify excision and to leave no longer in the text a passage of complete incomprehensibility to reader, actor and audience alike.”

– C. J. Sisson. New Readings in Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956. p. 191.

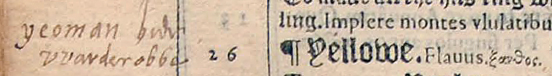

Malvolio’s line containing “yeoman of the wardrobe” is a fine example of a Shakespearean text that links in a rather extraordinarily direct way to our annotated Baret: Y26. annotator adds yeoman vide warderobbe in margin.

The text here referenced by the annotator is unmarked at W63.

Wardrobe: yeoman of the robes, or that keepeth the wardrobe chests.

Four distinct elements from this text appear in back-to-back lines in Sonnet 52:

So am I as the rich whose blessed key,

Can bring him to his sweet vp-locked treasure,

The which he will not eu’ry hower suruay,

For blunting the fine point of seldome pleasure.

Therefore are feasts so sollemne and so rare,

Since sildom comming in the long yeare set,

Like stones of worth they thinly placed are,

Or captaine Iewells in the carconet.

So is the time that keepes you as my chest,

Or as the ward-robe which the robe doth hide,

To make some speciall instant speciall blest,

By new vnfoulding his imprison’d pride.

Blessed are you whose worthinesse giues skope,

Being had to tryumph, being lackt to hope.

Any argument for these being simple words of little consequence collapses under the awareness that both keep and chest and robe and chest are combined in Shakespeare only in Sonnet 52. Such textual observation charmingly reinforces the pattern we observe throughout, but is nothing compared with the possibility that the long-standing confusion over the name Strachy could be resolved. Let us bring back, this time with the visual from the Baret, the annotation: yeoman vide warderobbe.

The neighboring word to the annotation, yellow, lands directly and symbolically in the scene where Malvolio speaks the “yeoman of the wardrobe” line. Moments after using this phrase he reads Maria’s letter (mistaking the handwriting as Olivia’s) that requests for him to appear, forever to the delight of audiences, in yellow stockings. The annotator’s entering of yeoman vide warderobbe alongside Baret’s printed entry for yellow matches the mind of an author who has a character utter “yeoman of the wardrobe” while knowing (before anyone else does) that this very character, his creation, will soon be wearing yellow. It would be one thing if Shakespeare used yeoman and wardrobe together on a regular basis under varying circumstances. But he does not. The one time he has a character use these words together, there is absolutely no hiding from the fact that it immediately sets in motion the brightest, most repetitive (9 of 29 usages), and most memorable presence of yellow to appear anywhere in the canon.

The connection to the name Strachy is less immediately apparent, but if we examine scholarship that extends from the late eighteenth century to the present, the relationship between the annotation and the printed text is truly uncanny.

George Steevens was the first editor to argue that the name “Strachy” could in fact be “Starchy.” Just recently, David Frydrychowski follows Steevens’s suggestion and takes it a step further, making a case for Shakespeare referencing Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, “whose household was linked in the popular mind with a certain fashion of yellow starch” (emphasis added).[i]

Frydrychowski further deconstructs the puzzle, thusly: “Given the hard pronunciation of ‘ch’ that survives in some instances from Middle English, an aspirated schwa or neutral vowel following the ‘ch’ might have formed part of the usual pronunciation; it is possible that the intention is simply to render what a modern reader would parse as ‘Lady of the Starch.’ [Interestingly, if the actor playing Maria gave a similar pronunciation when talking of the gulling of the hapless steward, the (doubtlessly intended) ‘yellow stockings’ would have been aurally indistinguishable from ‘yellow starchings.’]”[ii]

It would, no doubt, represent something different had our annotator added “Starchy” below yeoman vide warderrobe. Such an annotation would imply either a later reader or the writer actively working. But what we have is, we believe, even better. It is the future writer working as a reader.

[i] David E. Frydrychowski, “ ‘Some Old Story’: A Conjecture on Malvolio’s ‘Lady of the Strachy.’ “ Unpublished manuscript, April 22, 2009, abstract, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1925153.

[ii] Ibid, 6.

For Beehive Blog updates, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.