Spoken and Mute Annotations in Action

how the annotations can be looked at in relation to Shakespeare’s language

As a case for how the annotations can be looked at in relation to Shakespeare’s language and work, we have culled the following spoken and mute annotations from four separate locations in the dictionary, and included a neighboring text that is unmarked but may be suggested as having entered the annotator’s mind during the course of his time with the book.

G557. GRIND, annotator adds “a grindstonne.”

G557. GRIND, annotator adds “a grindstonne.”

F426. o: Go fetch trenchers.

F426. o: Go fetch trenchers.

P468. o: A saucer, a plate occupied at the table for a trencher.

P468. o: A saucer, a plate occupied at the table for a trencher.

W89. WASH… fetch, or geue me some water to washe my hands

W89. WASH… fetch, or geue me some water to washe my hands

W104. WATER… Grindstones going in troughes of water… He that fetcheth water in a bounge:

W104. WATER… Grindstones going in troughes of water… He that fetcheth water in a bounge:

Certain words have been highlighted to more easily illustrate the parallels in Shakespeare. Let us begin with Caliban, delivering a crazed, fiery song and dance protest, from Act 2 of Tempest.

Tempest. Caliban (2.2)

No more dams I’ll make for fish

Nor fetch in firing

At requiring;

Nor scrape trencher, nor wash dish

‘Ban, ‘Ban, Cacaliban

Has a new master: get a new man.

Freedom, hey-day! hey-day, freedom! freedom,

hey-day, freedom!

It may soon be argued that fetch and trencher belong together (so to speak) in the language of the period, therefore we should not be surprised to find them in these lines, along with additional words (water and dish) also associated with fetch and trencher.

But what happens when we consider the spoken annotation (at G557) “a grindstonne,” text that it can be demonstrated, via the mute annotation (at W104), that the annotator has drawn from a far removed location wherein the elements grindstones, fetch, and water are all found.

“Grindstone” itself is used only as a servant’s name for this one First Servant’s speech in act 1 of Romeo and Juliet and simply to introduce the hectic preparations for the Capulet feast where Romeo makes his appearance a few lines later. Let us look at the scene:

Romeo and Juliet (1.5.1–9; FF ee5)

FIRST SERVANT:

Where’s Potpan, that he helps not to take away? He shift a trencher? he scrape a trencher!SECOND SERVANT:

When good manners shall lie all in one or two men’s hands and they unwashed too, ‘tis a foul thing.FIRST SERVANT:

Away with the joint-stools, remove the court-cupboard, look to the plate. Good thou, save me a piece of marchpane; and, as thou lovest me, let the porter let in Susan Grindstone and Nell. Antony, and Potpan!

The speech of the Second Servant mentions the foulness of “unwashed hands.” Looking directly across the gutter to the previous page from where grindstonne is taken in the Baret dictionary, we find entries for wash. One of the subsidiary definitions toward the bottom of the page notes “fetch, or geue me some water to wash my hands.”

When we go back to the First Servant’s opening sally, what do we see? “Where’s Potpan, that he helps not to take away? He shift a trencher? he scrape a trencher!” His next speech includes “plate” and the single mention of “grindstone.” Trencher, plate, and unwashed hands are all in there with Susan Grindstone, and fetch is brought back years later in Tempest, to complete the cluster echo. Is it possible that the annotated Baret has provided the answer for how Shakespeare came up with this, seldom-considered, character’s name?

While we may never know the answer to that question, the argument for Shakespeare as annotator is more than any one example, or collection of examples. Such a case as the one just provided merely illustrates the process by which verbal parallels and echoes were located time and time again. Ultimately, it was the combination of all the evidence; evidence which includes distinct personal traces and the overpowering suggestiveness of the trailing blank; that allowed for the probability that Shakespeare was the annotator (and not a nameless annotator either familiar or unfamiliar with Shakespeare’s works), marking his copy of Baret over an indeterminate, but clearly substantial, period of time.

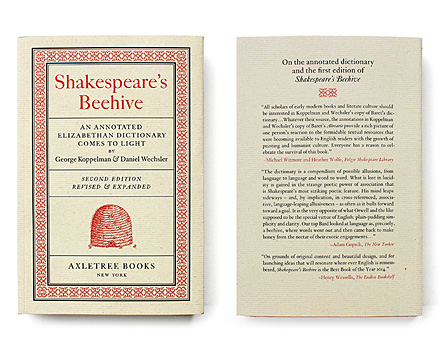

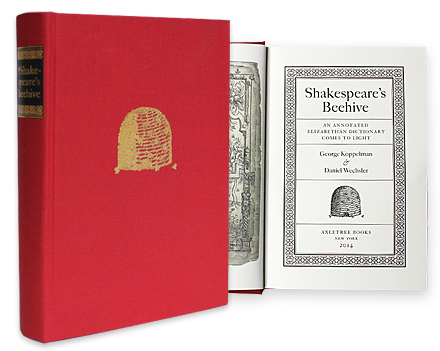

A Compleat Recording of the Annotations: This document is a compilation of every mark that the annotator has made in Baret’s Alvearie (apart from some much later markings in pencil that appear in one index), and is divided into four sections, according to annotation type. A PDF of the Recording of the Annotations (384 pages) is available upon request to anyone who purchases a copy of Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light.