May 1, 2014

The Poet’s Hand

By my life, this is my lady’s hand these be her very C’s, her U’s and her T’s and thus makes she her great P’s. It is, in contempt of question, her hand.

– Twelfth Night [II, 5] Malvolio

Voices from Adam Gopnik to Jonathan Bate have not been shy in publicly asserting that the hand in the Baret does not match the poet’s hand; the poet, of course, being Shakespeare. We feel it is important to clarify what components of the “poet’s hand” are being referenced.

Of all the books that Shakespeare could possibly have owned or used, not a single book with annotations is said to have survived. There are a number of volumes that have been attributed to Shakespeare’s ownership from the presence of a signature, but these signatures – and by extension the books – remain in dispute, and none contain annotations that are currently argued to belong to the poet. If Shakespeare did mark his books, books that we know he must have read, they either did not survive, or they are still out there to be discovered. One thing that we must all agree upon when referencing the “poet’s hand” when it comes to marginal annotations, and that is this: we have no means for comparison.

The “poet’s hand” is a reference to six signatures, all on legal documents, made during the later years of Shakespeare’s life, and two words, “By me” preceding one of the signatures on Shakespeare’s will. There is a fair amount of variability, even in the spelling of the signatures, and the variability – whether in spelling or in letter formation – can be ascertained even by someone who is not an expert in Renaissance paleography. And yet in spite of their differences, the six signatures are all written in what falls under the Secretary hand of the period; the “poet’s hand,” in other words, if we did ever see it written in the margins, should be compatible with this script, and not the Italic hand that would eventually take over, and with which we are today familiar.

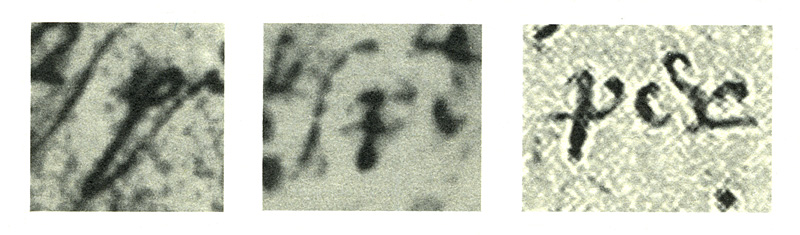

There is one signature, however, that needs to be addressed, and our effort at highlighting this particular signature in our book has yet to be publicly considered. On back-to-back days in March 1612, two signatures of Shakespeare are recorded on mortgage documents. They are in appearance so different that Edward Maude Thompson of the British Museum felt it necessary, early in the 20th century, to explain that the second of the two signatures (“C”) was written in an unusual style as a result of the small space allotted by the mortgage seal, thereby requiring Shakespeare to use “disconnected letters”. It is with this signature – the cramped signature – that we find sympathetic comparisons with annotations from our Baret, often made within similarly sized cramped spaces.

Consider the strikingly different formation of the two “p’s” – written on back to back days – and compare the second of these (from signature “C”) with an annotation in our book.

Signatures B&C, with a similarly sized annotation from the annotated Baret

The “ha” in Shakespeare’s signature “C” bears equally sympathetic comparisons with several annotations (including “Shaft” highlighted in our book and visible above the printed Shake in Baret), and a number of the annotator’s added words ending in “spe” are not dissimilar from the “spe” in the same signature.

Of course similarly generic annotations from other writers could be borrowed to the same effect. But what these examples illustrate is the extreme difficulty in eliminating an annotator based upon perceptions of how their signatures would correlate to marginal notations, even when we take from one of Shakespeare’s own signatures written in Secretary. The Folger voiced in its own blog, Collation, their agreement with our overall assessment: “As K&W (Koppelman and Wechsler) note, it is notoriously difficult to draw conclusions about a writer’s style of handwriting based on marginalia alone.”

In spite of this difficulty, the bias that argues Shakespeare would have relied on Secretary script alone persists, based not just on the signatures, but on Hand D (three pages in the collaborative, anonymous play Sir Thomas More that are thought by many to be Shakespeare’s contribution), as well as compositor errors that are felt to be a result of misreading letters written in Secretary.

But why argue that Shakespeare used exclusively a secretary script when using a variety of hands was common at the time (and still is)? Does any other writer of the period make, in his own writings, so much of the variation in handwriting as Shakespeare? Just think of the crucial scenes in some of the greatest plays, Hamlet, King Lear, and Twelfth Night, where hands are altered or confused. If Malvolio has trouble properly identifying and attributing c’s and u’s and t’s and p’s, surely the author of the play was aware that they could be made different, and may even have delighted in making them different himself. On the trailing blank, which combines Italic and Secretary, cursive and non-cursive, the annotator pens no fewer than six distinctly different p’s.

Why not allow Shakespeare, the ultimate example of a person mesmerized by words, to share the same excitement for letters? Letters are, after all, the stuff that words are made of.

For Beehive Blog updates, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.