Among the most heavily discussed and analyzed annotations in our copy of Baret during the first week of unveiling have been two words that appear side-by-side on the trailing blank. The busy bees responsible for bringing to the public’s attention a possible misreading are Aaron Pratt and Eve Siebert, each of whom has written a piece dissecting our transcription and our understanding of the annotations. We thank them for having taken the time to look so carefully at the annotated dictionary in question, but feel it is necessary to offer some clarification as, in each instance, only a partial screen grab has been selected and made public. The reduction of the image sells their arguments short, as well as ours.

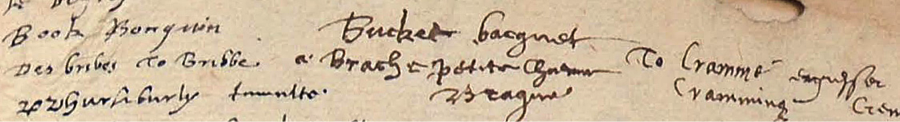

In our chapter on the trailing blank, we discuss in some detail the words on this page and the preponderance of echoes that are heard within the select group of plays wherein Falstaff appears: the two parts of Henry IV and The Merry Wives of Windsor. These three plays were written within a few years leading up to Shakespeare writing Henry V, the play that features, by a wide margin, the highest concentration of French usage in the canon. The fact that the annotator is fiddling with French and English usages and synonyms is only part of what makes the page so compelling. Many of the words (beginning with “bouquin” – visible in the image here) contain multiple meanings, but that is only one of the linguistic engagements at work. The annotator is demonstrably playing beyond the meanings of the words, as we attempt to make clear in our full chapter. The sounds, even the spellings are of added importance, and a careful, non-rushed analysis recognizes that the annotator’s intricate sideways glances are as significant as those glances that are direct.

Let us examine the work that was done by Mr. Pratt and Ms. Siebert and illustrate the deficiency in the cut-and-dry conclusion they both have arrived at, in part thanks to the truncated pictures they included with their analysis. With the slightly larger screen grab that we offer here, everyone can see that the word almost immediately to the left of the annotation is “bribe” and the word to the right is “cram”. Bribe and buck combine only one time in Shakespeare – Falstaff in Merry Wives; Cram and basket combine also only one time in Shakespeare, and again – Falstaff, Merry Wives. Same play, same character. And that is the play and the character that dominate the entire page.

Why then would both Mr. Pratt and Ms. Siebert choose to crop the annotation to eliminate important information? Their contention is that the annotation does not read “Bucke-bacquet” but instead reads “Bucket bacquet,” in their views, a simple English French combination with no relation to the other words on the page. But even if that is argued to be true, why eliminate what was stressed in the chapter and can be seen in the image if you allow it to slightly expand?

The question is, do the connections with bribe and cram amount to nothing but a coincidence? If the annotation has been falsely read; that is, if the annotator has simply added the French for bucket alongside the English word bucket without any further connection to the other words on the page, then the connections involving bribe and cram with buck-basket (our interpretation) must necessarily be explained away as a convenience – another coincidence to help insist on the tie between Merry Wives and the words on the page. But what are the odds of each word combining with the neighboring word only one time in Shakespeare, and in the same play, and voiced by the same character? The remaining evidence on the page offers discernable support to the contention that the annotator, whoever he was, had Falstaff and Merry Wives on the brain, with clear thoughts of the Henry IV plays and pre-allusions (our argument) to Henry V.

And yet we are accused of having “botched” this transcription, an annotation that would otherwise send a strong message connecting the trailing blank to the works in some way, given the coinage of “buck-basket” by Shakespeare and its six usages in Merry Wives.

Mr. Pratt and Ms. Siebert read it as a simple “Bucket bacquet”, but even if the annotation began there, the annotator knows of other possibilities from looking at the annotation on the page and hearing it ring in his mind. Our argument is that the annotator can see and hear and understand things in multiplicity (it takes an active brain), and whether “Bucket bacquet” or “Bucke-bacquet,” appears in one’s own transcription of the page, the neighboring words are no accident.

To help reinforce the idea that the annotator is channeling buck-basket, we turn to the Baret itself, and note the intriguing alternate spelling in English under Baskette; a maker of Basquets. Variability in English spelling at the time raises the distinct possibility that the second half of the annotation can be interpreted as a Middle English substitute for the word basket, and that the annotator is aiming for buck-basket all along. That is, in our opinion, clearly where he ends up, but how he arrives there may indeed be through the fiddling with words that is his trademark – a constant fiddling and fascination that takes place throughout the entire book, not merely on the trailing blank. Words can achieve multiple purposes with the flick of the tongue or the slight adjustment of the quill. You see this all up and down the page: the playing with meaning and sound and even visuals. Whoever the annotator was, The Merry Wives of Windsor is at the forefront – either through coincidence or reflective linguistic choice – on this strange page we refer to as the trailing blank.