July 11, 2014

Henry Denham and Abraham Fleming

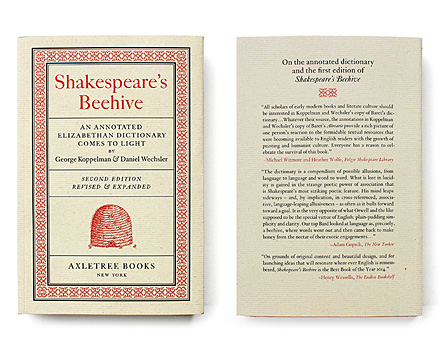

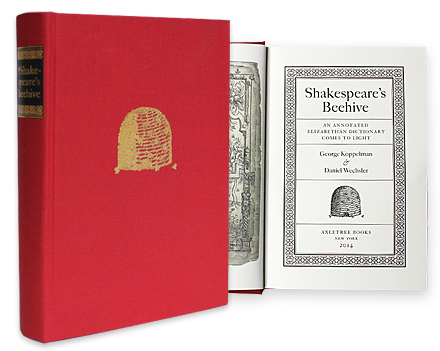

In our study, Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light, we raise the possibility that if Shakespeare did come into contact with Henry Denham vis-à-vis employment (as was once previously claimed), he may well have had access to the preparation behind the issuing of Holinshed’s Chronicles in 1587, which, as with the 1580 Alvearie, was printed by Denham. The 1587 edition of Holinshed, the second edition, was the version Shakespeare consulted and drew from throughout his career as a writer, most notably as the primary source for the English Histories over the early portion to middle point of his career, but also as a reference for later works, including the great tragedies, Macbeth and King Lear.

In the time since the release of our study, and the first reporting of our claim in The New Yorker, we have examined more carefully the striking parallels between the Holinshed of 1587 and the Baret of 1580.

The principal participants in revising and ushering forth these two source books (one long famous, the other still largely unheralded) are identical. Both works are second editions printed by Henry Denham, published after the original main compiler has died (Holinshed in 1580, Baret in 1578), and on each occasion, during the process of expanding and polishing the work, Abraham Fleming is hired as the editor. Fleming (1552?-1607) is known today by few people, even academics familiar with the period, in spite of having carved out a busy and distinguished career as a clergyman, writer, translator, editor, and poet. There is a good chance that Fleming was present at, and even conducted a portion of, Christopher Marlowe’s funeral, reasoning that is based on his position as curate in the parish of Deptford during the time when Marlowe was murdered and buried there. That was in May of 1593, and is mentioned more for curiosity’s sake. Fleming’s most important and lasting contribution was the job he performed on the second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, a job that began in 1584 when the project commenced. In addition to serving as the primary editor and proofreader, Fleming contributed with his own extensive enlarging of the third volume and the creation of detailed indexes.

Denham, who we may assume appointed Fleming as the Holinshed revisions got underway, must have been impressed with how Fleming had previously embellished Baret’s Alvearie. Among these contributions were the assembling of over 200 proverbs not printed in the first edition, the inclusion of a proverbial index, and the addition of Greek, transforming it from a triple dictionarie to a quadruple dictionarie. Granted, the fact that the two individuals most responsible for the second edition of Baret’s Alvearie were central in the development and release of Shakespeare’s most famous source book may indeed be nothing more than a coincidence, but it does contribute as a part of the backdrop in making our argument and reconstructing how Shakespeare would have originally acquired a copy and in what context.

Taking the stance that Shakespeare worked for Denham, without hard proof, can give rise to grumbling, especially considering the bold (some might contest, dreamy) assertion we make in our study: that Shakespeare acquired our very copy through this connection and began annotating the volume during his early years in London (possibly under the umbrella of initially helping to create a third and never completed edition), before squirrelling it away amongst his favorite books, where it could still prove useful as an occasional reference tool. Charging this conclusion to be conjectural and self-serving is one thing, let us remove our particular copy of Baret from the equation, and ask a relevant question: How would Shakespeare, the boy from Stratford, been expected to get his hand on a set of Holinshed? Although there is no generally accepted consensus as to when exactly Shakespeare arrives in London and soon after begins a life in the theater, we can be sure that there was no set of Holinshed stuffed in with his belongings upon arrival. Baret’s Alvearie, as anyone who has handled a copy knows, is a big book, roughly 1,000 pages thick and measuring approximately 12” x 8”. Holinshed was considerably bigger still, and issued in two or three volumes depending upon the binding. Given the relatively slender time frame between the publication date (1587) and the composition of the first group of plays (the three Henry VI plays, 1590-1) indebted to this source, Shakespeare must have, at the very least, had access to a copy not long after publication. Gaining employment via the world where books were being prepared for print is hardly outlandish, and would make sense for someone who was hungry for books, and would be so reliant upon them to aid his writing process. An alternative, that Shakespeare had access to the library of a patron, is possible, but such a benefit would more likely have occurred at some point later, after his talents in the theater had emerged (not something that happened overnight) and he had settled into a life of writing and acting. It seems more believable that the reading and acquisition of books, so necessary to his development, already had to some degree begun in earnest prior to the involvement of a patron such as Southampton. The library of a preexisting friend is a possibility, especially if we imagine Richard Field as that friend; certainly an awareness of his being in London, and a connection to Field from their days together in Grammar school, would have facilitated for Shakespeare an opportunity in gaining access to the book/print world.

If, at some early moment in London, Shakespeare did get in with Henry Denham and his associates, the connection would have given him some necessary parts (including Holinshed and Baret) of the toolkit (to borrow from Henry Wessells) that he took along once he entered the theater and began to make a name for himself. The sourcebooks themselves were not liable to be lying around at the entrance to the theater. If we take Holinshed as one example, either Shakespeare managed quick and repeated access to someone’s library to begin absorbing the material, or he could have gotten a jump-start on his reading while working on a copy as it was being prepared. There were later editions of Cooper’s Thesaurus (another book thought to have been used by Shakespeare and printed by Denham) but no later Barets. So perhaps the examples of proofreading in our copy represent the beginning of a 3rd edition that never came about. We suspect Shakespeare was a part of a “proofing” group, and acquired his copies of Baret and Holinshed through the book world, an introduction to which he was likely given by Field. Thus were registered some of the initial deposits into Shakespeare’s library.

For Beehive Blog updates, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.